From underground newspapers to the best-sellers list, Robbins’ work was irreverent, meandering, and hilarious. His nonlinear narratives and unrelenting “goofiness” allowed him to follow his flights of fancy, whether they be treatises on religion or his LCD-laced philosophy. His first novel, 1971’s Another Roadside Attraction, takes a series of diary entries to reveal the author’s whimsical worldview as his characters steal the mummified corpse of Jesus Christ. The book was a sleeper success, followed by Even Cowgirls Get The Blues, about a female hitchhiker making her way to a South Dakota women’s spa, later adapted into a film by Gus Van Sant.

The unique soup Robbins was born into helps explain his eccentric novels. Born July 22, 1932, Robbins grew up with a “typical dysfunctional family.” The descendent of a “long line of preachers and policemen” was raised in the Richmond, Virginia suburbs by an electrical company employee and a nurse. He spent one summer working at a circus, he said, scrubbing the backs of beasts, which turned out to be a good metaphor for writing a novel. Robbins studied journalism at Washington and Lee University for two years before being drafted into the Air Force in 1953. He spent two years as a meteorologist in Korea until he was discharged in 1957. Upon returning to the U.S., he re-enrolled in school, this time at Virginia Commonwealth University, then called the Richmond Professional Institute. There, he started working for the college newspaper and, after graduation, worked at the sports desk for the Richmond Times-Dispatch, testing the Jim Crow era restrictions against publishing photos of Black performers. He was fired when he published a picture of Sammy Davis Jr. with his wife, Mai Britt.

In the early ’60s, he moved to Seattle to get his master’s at the University of Washington and began working as an art critic, publishing for The Seattle Times, Art In America, and Artforum. As the legend goes, it was around then that Robbins convinced a pharmacology professor to let him drop acid for the first time. Robbins spent the day in a chair, unable to move except for trips to the bathroom. He considered it one of the most rewarding days of his life. Unable to read or write for the next six months, he used the mind-expanding experience to justify quitting his day job and beginning to write for underground newspapers. Following a successful review of a Doors concert, in which he found his voice describing the band as an “early cunnilingual, late patricidal, lunchtime in the Everglades,” Robbins set to work on his first novel.

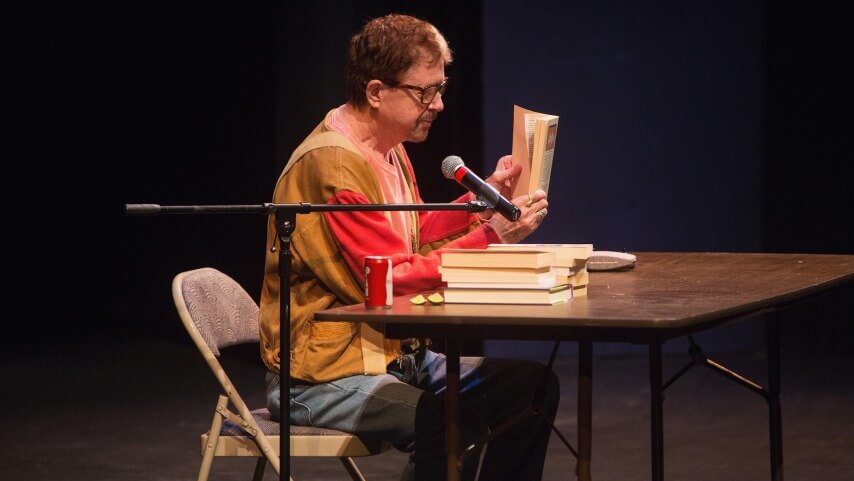

Robbins was a slow writer, often spending hours on a single sentence and churning out about 500 words a day. Across his career, he published eight novels, including Jitterbug Perfume, Half Asleep In Frog Pajamas, the Wild Ducks Flying Backward collection, and the 2014 memoir Tibetan Peach Pie: A True Account of An Imaginative Life. His final novel, Villa Incognito, came out in 2003. The A.V. Club called it “unpredictable and enjoyably excessive.”

Robbins is survived by his fourth wife, psychic Alexa D’Avalon, three sons from previous marriages, and a grandson.

![Rob Reiner's son booked for murder amid homicide investigation [Updated]](https://img.pastemagazine.com/wp-content/avuploads/2025/12/15131025/MixCollage-15-Dec-2025-01-10-PM-9121.jpg)