The year's biggest fantasy trend finally gives women swords

No one in any of this year's lady knight books is waiting for someone else to determine or change their fate.

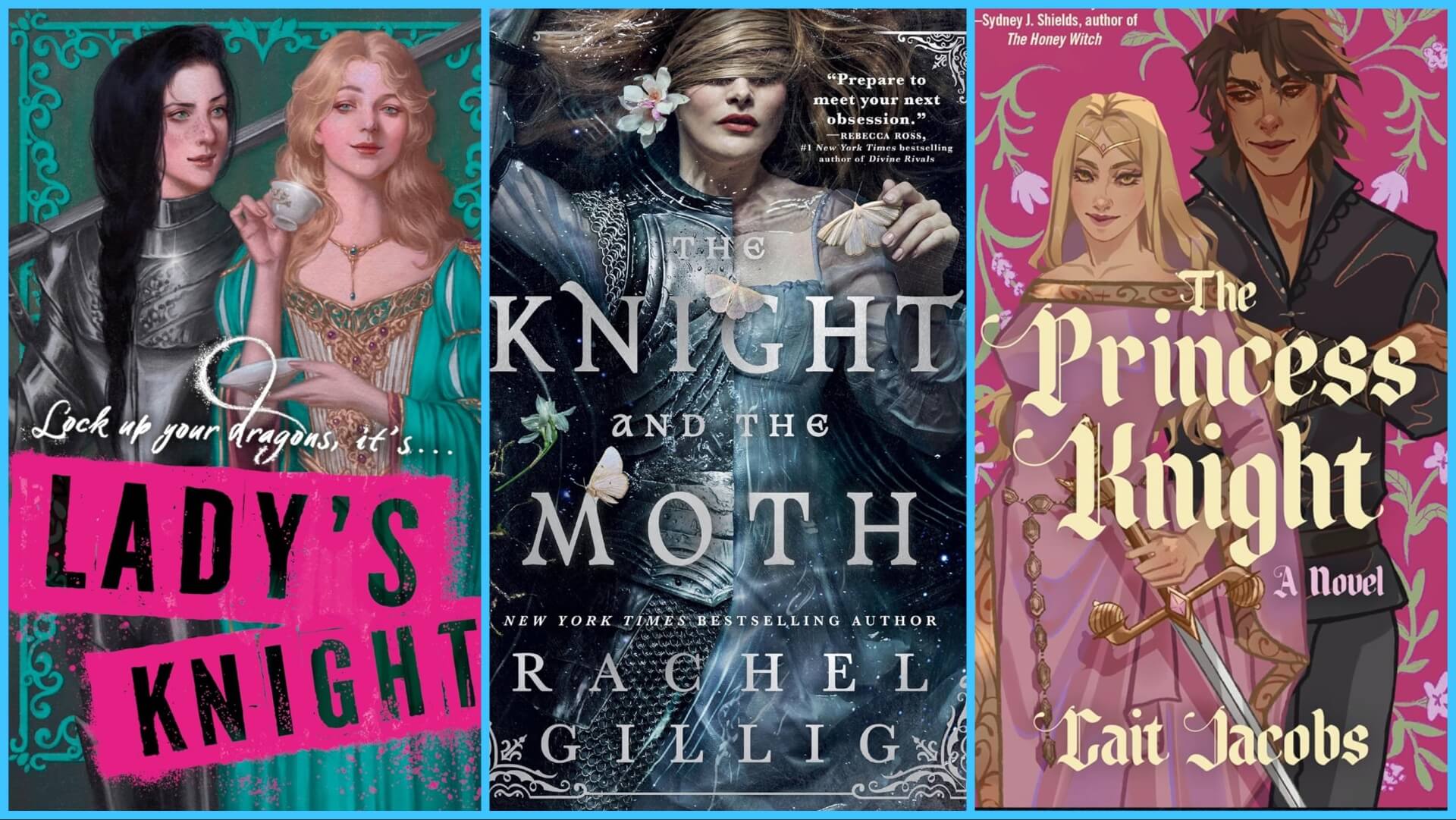

Left to right: Lady's Knight cover (Image: HarperCollins); The Knight And The Month cover (Image: Hachette); The Princess Knight cover (Image: HarperCollins)

In the year of our Lord 2025, the medieval era is having a moment. This hasn’t come out of nowhere—last year, Chappell Roan literally set the stage on fire at the MTV Video Music Awards while performing “Good Luck Babe” dressed in armor and chain mail, while Pinterest (accurately, as it turns out) predicted the rise of “castlecore” as a decorating and fashion trend. But while medieval themes, aesthetics, and characters have been around in popular fiction forever—titles ranging from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord Of The Rings to Robin Hobb’s Farseer trilogy and George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice And Fire books have all taken inspiration from various familiar aspects of the period—the medieval renaissance that’s taking over the publishing industry at the moment feels like something brand new.

Much of this can be credited to the rise of the sub-genre known as romantasy, a deliriously popular style of story that combines the elaborate world-building and intricate magical systems of high fantasy with the relationship arcs and steamy sex of romance. These books not only feature strong female leads with complex problems and emotional traumas, but they also give them the power to change their fates, often setting them against specifically patriarchal or other oppressively dystopian systems and allowing them to save kingdoms, marry fae princes, and ride dragons in the process. Given the largely awful state of, well…pretty much everything at the moment, it’s not a huge stretch to see why such stories are so popular, and seemingly growing more so every day. After all, taming a mystical beast can’t be all that much harder than some of the things young women are asked to deal with regularly in our world right now.

But while this corner of the fantasy world has embraced everything from faeries (Sarah J. Maas) and dragons (Rebecca Yarros) to vampires (Carissa Broadbent) and mythological gods (Abigail Owen) over the past few years, 2025’s so-called “lady knight” trend has emerged as one of genre’s most original and satisfying. Nearly a dozen different titles featuring women sporting armor and brandishing swords have hit shelves this year, with stories that have run the gamut from young adult and romantasy to epic fantasy and folk horror.

From lyrical and bittersweet fairytale The Isle In The Silver Sea and the more Gothic-tinged The Knight And The Moth to the youthfully exuberant Lady’s Knight and the timey-wimey The Everlasting, these are all stories that gleefully subvert expected stereotypes, shake up traditional gender roles, and put the kinds of queer and marginalized characters who rarely feature in this particular fictional space at the center of their narratives. It helps, of course, that these books are all great as stories, each with compelling characters and satisfying plots. But at this specific cultural moment, these books—and the larger medieval-themed renaissance they represent—feel like a reclamation, a statement about who we want to be and what kind of world we want to live in.